PAKISTAN: WATER CRISIS AND A POTENTIAL WAY OUT – Part III

Posted on 27. May, 2010 by Jeff in Letters to Editor

By Barrister Mansur Sarwar

D3. Additional Confidence Building Measures for Implementing Water Apportionment Accord of 1991: What a strange irony of fate that the measures that we demand from India as lower riparian country, at national front, all stake-holders are hesitant to practice. As a matter of fact, Accord of 1991 provides unique opportunity and challenges all national stakeholders to demonstrate that they are capable of thinking creatively for coming up with new and effective confidence building measures on their own. At the next step, they should be courageous enough to put in place and implement all such new confidence building measures to eliminate fears and reservations regarding water distribution among the four units of Pakistan to end the ongoing blame game against each other.

At national level, Punjab being an upper riparian entity for Sindh and relatively dominant province of Pakistan, it replaces India in the local context while taking driving seat to operate water train with most control in its hands. Here is litmus test for Punjab to set a good example by avoiding train wreck as stated before. What Professor John Roscoe proposed to India as a dominant upper riparian state while explaining feelings in Pakistan, I repeat the same, with appropriate alterations, to the People of Punjab that there must be some courageous and open-minded of Punjabis – in government or out – who will stand up and explain to the public why this (Water) is not just an issue for Sind, but why it is an existential issue for Sind. Similar statement goes for the people of Sind when their role as upper riparian entity is considered for some parts of Baluchistan. Perhaps this could help to create conducive environment for rational discussion among all concerned.

To be fair with all stakeholders in Pakistan, water is equally a matter of existential issue for Punjab too. As a matter of fact, such desperation for water by all concerned stakeholders in Pakistan could be made a positive factor to understand concerns and reactions from the lower riparian provinces. However, history does not support this positive approach. Instead, narrow but emotional, self-serving alternatives are being cashed in to promote parochialism for political gains. However, such self-destructive politicization of technical issues of water acquisition and distribution has not helped at all in facing water crisis and if we continue to follow the same irrational path in the future, I am afraid that we will be playing in the hands of those people who wish that Pakistan, California of Asia, to be converted into Somalia of Africa. If that happens, we will not be able to blame only outsiders as we keeping on claiming more and more, even un due, rights but always refuse to shoulder corresponding responsibilities for averting such water crisis.

`As stated before, Water Apportionment Accord of 1991is a great achievement in securing consensus among four provinces of Pakistan where discard is a common phenomenon but accord is an unheard commodity. This was based on brute give and take and hence this consensus based agreement must be adhered and strengthened as a way out to plan and implement water projects as per allocated water resources for each province.

On one hand, there are people in Sindh who cry foul over this agreement and claim that Punjab took undue share of Indus water under this agreement. On the other hand people in Punjab have their own grievances. For many Punjabis, in the Indus Valley, where, as per accepted and implemented principle of basic design for its irrigation system, water must have to be distributed equitably based on area irrigated; is it fair that with 75.5% of total irrigated area of Pakistan in 1990-93, Punjab only gets 47.67% of total water allocation? This is especially causing severe heart-burning when Punjabis see that Sindh got only 15.5 %of total irrigated area at time of this Accord but it received 41.55% of total water allocation from the Indus River System. In their view, as agriculture sector was using 97% of total water available, this operational rule must have been followed instead of historic claims which lost relevance with the establishment of modern weir-controlled canals designed for equitable water distribution based on area irrigated instead of inundation canals of the past and then partitioning of the Indus Valley and singing of Indus Water Treaty between India and Pakistan changed all previous precedents. Had the water allocations for 97% amount been made equitably based on area irrigated and remaining for remaining 3% amount on population basis, it would have been an agreement based on fairness.

However, above stated thoughts are either suppressed feelings in view of the potential threats to the federation of Pakistan or just after thoughts as water crisis keeps becoming alarming every day. As Punjab signed this Accord, as a law abiding people of Pakistan, such after thoughts are alright to demonstrate the extent of compromise and sacrifice made by the majority group for minority group of one country, no second thoughts be allowed to unsettle an already settled issue on consensus basis. As a matter of fact, we should remind ourselves that a consensus building process always requires some give and take and politically sharp people with proper home-work usually extract maximum benefits.

For Sindh, securing more than fair share based on consensus in the emerging scenario of severe water scarcity is a monumental success. At present, instead of crying foul to claim more, it would make much more sense if they invest their extra efforts for devising and implementing credible confidence measures to have their share of water distributed as per the Accord of 1991.

In line with similar argument, Baluchistan should be given the same right to have all such CBMs put in place in Sindh for getting their agreed water share as Sindh wishes to have such measures to get its due share from Punjab and Khyber -Pakhtunkhwa. Some arrangements are already put in place but either they are not very effective or their functionality is questionable.

For example, as informed by a former irrigation secretary of Punjab, Sindh has its representatives appointed at critical control points of Indus River System to monitor actual water distribution as it happens. I am sure that such arrangement must have been on reciprocal basis. My proposal will be that we spend less time on criticizing a well-intended arrangement but invest more time and efforts to find root-causes and suggest additional adjustments or changes to make the existing arrangement as an excellent CBM.

Other case in view is the expensive telemetry system that has been installed to provide real time flow data at critical control points along the Indus River System. Only thing functional in this context is the ongoing blame game and not the telemetry system. Why did all investment go waste without producing intended positive results? No neutral or local entity has been made to study the failure of this excellent real-time monitoring system. My proposal would be that we set up a time-bound independent judicial commission or ask International Water Management Institute to study its real causes and suggest ways and means to make it work as per the satisfaction of all stakeholders.

IRSA, Indus River System Authority, is itself an excellent CBM between beneficiaries as far as this arrangement for water distribution is concerned. As compared to the Indus Water Commission, IRSA is much more effective in allocating water among all four contending provinces. In a natural environment of smaller provinces versus Punjab phenomenon, Mushraf put a Sindh based federal representative to the four members from all four provinces. In Punjab, such arrangement is perceived to be unfair for a province that produces almost 80% of granary of Pakistan.

For any arrangement to succeed and be sustainable, it has to be fair for all. In this context, a third party should be hired to study about the weaknesses of IRSA and propose measures that make this body a fair institution instead of a sort of inter-provincial semi-political game club where all dices are loaded against one province only. As cliché goes, only fair games produce fair results; let us ensure a fair and honest game for the sake of all concerned for all the times. If we wish to have non-controversial institutions, let there be more honest and transparent efforts be invested to make IRSA itself a confidence building measure for all four provinces.

In view of disharmony and discontent over water distribution, we have a long way to go before getting a satisfactory and functional system by putting all intrusive safe-guards in place at national level. If we manage to do so, our success at home will provide a clue to demand similar measures at the regional level under Indus water Treaty. In other words, if we are not fair and transparent in our dealing within one country, how can we demand a fair and transparent implementation of the Treaty from a not-so-friendly upper riparian and regional power that holds all the cards in the given context?

D4. Agreed and Efficient Supply Side Water management: International literature provides the following definition of Supply-Side Water management: “Supply side management means developing new water sources, building additional water storage facilities, diverting water from one basin to another, or treating water that might not otherwise be potable (e.g. desalinization)”. Perhaps Pakistan is one country where surface and groundwater infrastructure is well developed except for developing storage facilities to tackle seasonal excessive unevenness in river flows and institutional arrangements for proper surface and groundwater management. At present, Pakistan is utilizing almost 75 % of renewable water resources; an indicator of severe water stress situation compared to many other arid and semi-arid countries.

According to some reports, total groundwater potential of Pakistan is around 66.8 MAF (82.4 BCM). At a time when total tube-wells installed were 575, 197, it was estimated that about 62 % of total potential was being exploited. With tube-well population getting almost doubled, the residual potential for groundwater extraction is hardly of any significance; rather, it is possible that many areas have already started over-extraction of groundwater causing groundwater mining as a common practice.

Like in many relatively more developed countries, we can treat wastewater (sewage plus industrial wastewater) for its reuse in agriculture and / forestry. Based on an estimate of wastewater from important cities of Pakistan, current quantity generated is about 2.3 BCM. At present, only one percent is treated and the rest is either used for growing vegetables within peri-urban areas and / or disposed off into the adjacent rivers and canals. Either case, such practice is a growing health hazard. Although the current status of wastewater is not that huge when we compare it with surface and groundwater availability but it is large enough to get treated and used for plantation like promoting forestry in this country.

Another source worth considering is the rain water harvesting. Reports suggest that Pakistan has total potential of rain water harvesting as 8.5 BCM (6.9 MAF) but not more than 0. 0.12 BCM (0.1 MAF) is being availed at this time. Main source for rainwater harvesting being used in Pakistan is mainly small and mini dams. Only in Pothwar area, there is a potential of 400 small dams and around 8000 mini dams. At present, however, only 30 small dams and 405 mini dams are built in this area. As construction of such small and mini dams are mostly built for meeting local water needs, they are not controversial and water resource development using these small and / mini dams can be pursued without going through lot many socio-political road blocks.

However, the most significant contributor towards finding a way-out for meeting water crisis in country is increasing water storage capacity at a very fast track. However, we as a nation are in bind: On one hand, without building new dams for storing Indus River supplies, we have no future for our agriculture based economy; and on the other hand, without securing consensus among all four provinces for building new dams, we fear to run a risk for endangering our federation of four provinces. Parallel to this statement, I just cannot stop myself saying that not trying to find alternatives and creative ways and means to develop water storages is a definite sign of no future of any kind for Pakistan.

Of course, it is interesting report that Colorado River that has annual yield only 18.5 BCM (15 MAF), the storage along the river is around 80.2 BCM (65 MAF); almost five folds of the annual yield. Whereas our even divided Indus River System delivers around 179 BCM (145 MAF) to Pakistan and our water storage is hardly 15 BCM (12 MAF) with the same number of dams. Comparing with other similar international achievements, our performance is simply a huge embarrassment to say the least. Why cannot we have water reservoirs with total capacity of 900 BCM, according to the storage ratio of Colorado River, instead of just few peanuts of 15 BCM?

According to a cliché, I strongly believe: “Yes, we can.” Of course, I am not trying to suggest that finally there is a magical way-out for developing a consensus to build dams across Indus or its other main tributaries; no, under the prevailing political environment, it seems very difficult to achieve such breakthrough. However, things are not as gloomy as either they are painted or made to appear. Quite contrary, there are already two important provisions in place to facilitate a significant alternative way-out of the bind that we are in. Here, I am referring to the Indus Water Treaty of 1960 and the Water Apportionment Accord of 1991. If we decide not to build storages for irrigation across the Indus River or its main tributaries and devise a way-out based on these referred agreements; we have a win-win situation for all stakeholders in Pakistan.

As a clarification to above statement, I have only said that we should no more insist on building water storages for irrigation across the Indus River and / or its main tributaries. However, this does not stop us to have cascade of run-of-the-river hydro-power dams or even more than that hydraulic state to generate environmental-friendly and cheap electricity. With this rider, no sane person in the country will object as the energy dependency on imported fuel for producing many times more expensive power is suicidal for the economy in short as well as in longer run. As a matter fact, these alternatives were promoted to avoid or side-track efforts focused on building large multi-purpose reservoirs across our main river system. Once the bone of contention is removed, developing cascades of run-of-the-river or even more than the run-of-the river dams should not cause any significant opposition anywhere in Pakistan.

More than hydro-power, however, people are worried to death by the emerging threat to its irrigated agriculture because of severe shortages of water when required most and flood possibility when demand is low. This can be done either by design as India is planning and constructing dozens of dams on all three western rivers allocated to Pakistan and ignoring watershed management within its controlled region or because of on-going climatic change globally.

Yes, we can and we must work out joint projects and studies for effective watershed management both under Indian-control as well as those watershed regions that lie within Pakistan. We should also conduct research studies jointly with India to assess impacts of climatic change on our river flows and implement correct and proactive measures to deal with such potential changes. In addition, we must be more aggressive in making use of all mechanisms put in place under the Indus Water Treaty to ensure that the Treaty is implemented both in letter and spirit for the sake of people of this region.

However, a real success of such efforts will significantly depend on the conditions we create in Pakistan that help to handle all the emerging threats being made to disturb timing as well as river flows either by design through possible hostile actions of the upper riparian regional power or by the ongoing climatic changes. In this context, after forgoing option to build large reservoirs for irrigation on the Indus or its main tributaries, we are left with alternative of allowing each province of Pakistan take responsibility of storing its full or partial share as agreed in the Accord of 1991 off-channel storages.

In case of Khyber –Pakhtunkhwa and Punjab, both sides of the Indus River and Pothwar region can provide sites for off-channel water storages. Since Sindh and Baluchistan do not have such convenient off-channel storage sites, either they can have their own but paid storages say in Gilgit-Baltistan or jointly, based on agreed terms of reference, with Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa and / Punjab in Pothwar region. Because of the up-stream locations for off-channel sites, the present irrigation system can easily be connected with their respective canal system to augment flow during lean river flows. Since making use or storing water for its future use as per the Accord of 1991 is a provincial subject, provinces must be authorized to take necessary steps in this direction.

This proposed alternative is a significant component of the way-out from the emerging severe water crisis in the country. In a way, this presents a win-win situation to get of the hardened positions to a way forward as it caters to the most concerns of different stakeholders:

- Political stands of Sindh, Baluchistan and Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa provinces are accommodated by agreeing not to build multi-purpose dams on the main Indus or its tributaries ;

- Such an alternative will allow to build cascades of hydro-power dams on all main channels to generate cheap and environment friendly electricity;

- Inter-provincial tensions over water distribution during high demand periods should dissipate as the due quantity within season will take precedent as compared to weekly water distributions are practiced at present;

- Off-channel water storages in Pothwar area should provide convenient capacity to store flood water, under both natural as well as man-made scenarios, from all three western rivers in general and from the Jhelum and Chenab in particular; and

- This way-out helps to avoid blame game, right or wrong, against each other for water theft based on agreed water shares as defined by the Water Apportionment Accord of 1991.

Such alternative storages are must to make sure to face the emerging water crisis as well as trying to bypass the current standoff over building large dams on the Indus and its main tributaries. In view of the skewed nature of river flows, at present, our storage capacity is too limited. Based on 50% probability, flow data from 1937 to 67 reveal that almost 85% (144.5 BCM or 117 MAF) of total annual flow (173 BCM or140 MAF), occurs only during Kharif or summer season. In the absence of relevant data regarding the 2-3 months of Monsoon (15 June to 15 September), just to present a ground reality, we associate (based on IWMI’s data by Asim Rauf Khan, 1999) two-third or 96 BCM or 78 MAF flow during Monsoon. Even if we deduct 15 BCM required to fill the existing three dams, we still need to handle the remaining 81 BCM (66 MAF). Where do we have capacity to make use of this huge quantity of water, almost 47% of total annual flow of the Indus System?

Here I expect many challenges like how come that annual flows below Kotri are around 43 BCM or 35 MAF only? Of course, it is debatable but the same way someone else can point out that why the annual average of the Indus flow from 1922 to 1961 is reported to be about 115 BCM (93 MAF) and then we downgraded this average to about 77 BCM (62.7 MAF) from 1985 to 1995? Did India divert the Indus flow to cause such dramatic drop? Is there some explanation and account for 50 to 100% more quantity that every province is trying to push through their respective canal systems (based on data collected on three distributaries in Punjab, Sindh and NWFP in 1985 by a team of Colorado State University)? Of course, all such figures do not match Up; either our flow measuring means are incorrect or there are some other hidden agendas that we do not understand. In any case, we need to move forward and let each province be responsible for its own due share to get out of this hypocritical game that takes us nowhere.

One question that I have never been able to understand is as follows: Why the Colorado River System that has annual yield around 15 MAF but its storage is almost 5 times of its annual flow but the Indus System with annual flow being 10 times more than that of the Colorado River is cursed to restrict its storage capacity to only 10% of its annual yield? After securing the Indus Water Treaty of 1960 and Water Apportionment Accord of 1991, it does not make any sense to let the future of country be risked by not doing a doable as has been demonstrated along the Colorado River under similar semi-arid and arid environment and with same number of reservoirs. In view of the prevailing political logjam over constructing dams along our river system, it is proposed off-channel storages based on due shares of each province.

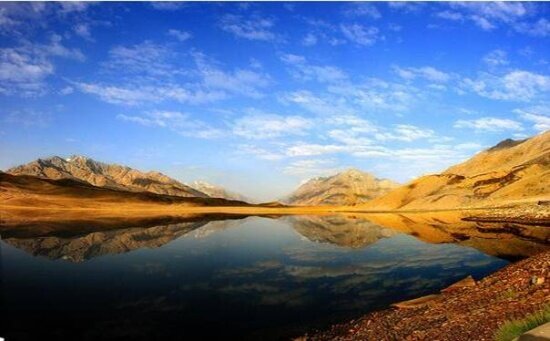

Do we have enough off-channel sites for such storages? Our hilly northern areas and plateau of Pothwar are ideally located options for such storages. Once people agree to seek off-channel alternative, surveys and studies can be conducted to find appropriate off-channel dam sites. In view of the topography of the referred areas, there will be no dearth of such sites. For example, as shown in Figure3, in Pothwar Area, some surveys have already been conducted to pin-point some locations that are suitable to store flows from the Indus River as well as Jhelum River. In case of Punjab, for explanation purposes only, 37% floodwater share amounts to 30 BCM or 24.5 MAF from all three western rivers.

loading...

Tweets that mention PAKISTAN: WATER CRISIS AND A POTENTIAL WAY OUT ? Part III | Opinion Maker -- Topsy.com

28. May, 2010

[...] This post was mentioned on Twitter by . said: [...]